All medical treatments have potential harms as well as potential benefits, and it’s important to be able to weigh these against each other. With vaccines, the benefits are particularly complex as they can involve benefits to others as well as to ourselves – and the harms can feel particularly acute because we take vaccines when we are healthy, as a preventative measure.

Potential harms:

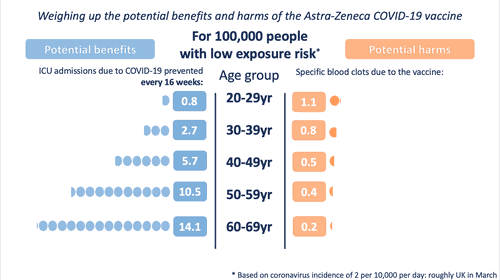

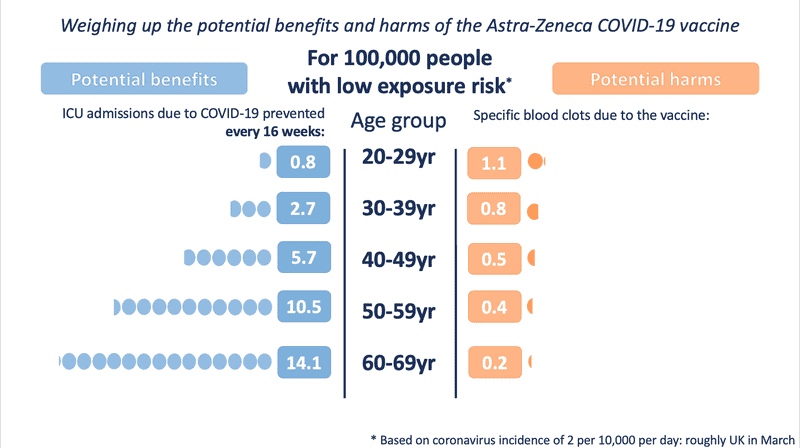

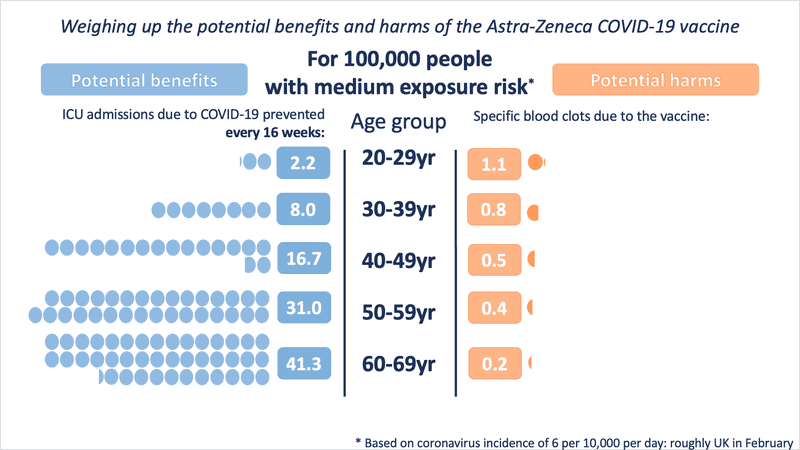

Following roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine from Astra-Zeneca, large-scale monitoring has picked up a potential link to a specific kind of blood clot. Cases of a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) have also been recorded, but for the Astra-Zeneca vaccine, cases are very rare, perhaps because of precautions being taken for those with known allergies. Other side effects are so far thought to be short term.

The MHRA data point to these specific blood clots being more common in younger people.

Potential benefits:

The benefits of the vaccine are protection against COVID-19 (short-term and ‘long COVID’) – for the person being vaccinated and for those they come into contact with as it also reduces the chances of them being infected by the vaccinated person.

These potential benefits, though, change according to:

- How likely a person is to be exposed to the virus (e.g. how prevalent the virus is, locally, at the time; what their occupational exposure is to it)

- How likely they are to have a poor outcome as a result of catching the virus (this is mostly affected by their age, but also underlying health conditions)

The potential benefits also accrue every day that the person is vaccinated (and exposed to the virus).

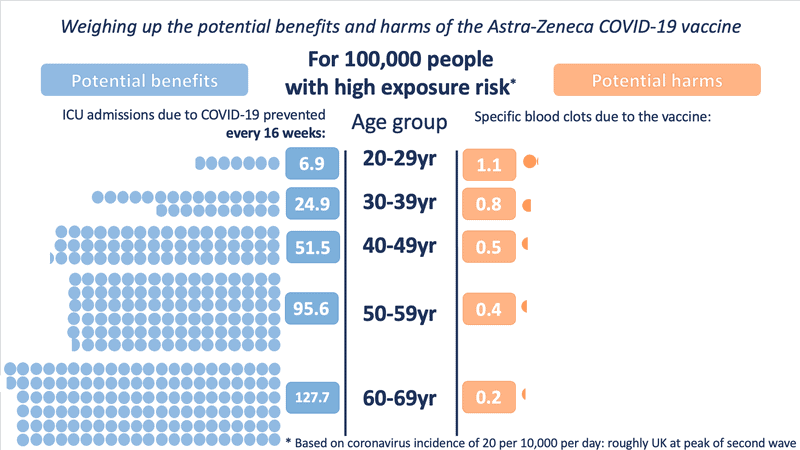

In order to illustrate the potential benefits weighed up against the potential harms, we wanted to choose ‘benefits’ that might be considered comparable to the most serious harms – those of the specific blood clots being discussed. We chose to illustrate the estimated number of ICU hospitalisations prevented by the vaccine (per age band). We also chose to illustrate three possible levels of exposure to the virus – each time illustrating the benefits accrued over 16 weeks.

So, we took:

For the potential benefit: incidence rates based on the Covid-19 Infection Survey, ONS, 1 April 2021. The proportion of hospitalisations in a cohort was calculated using the estimates of COVID-19 hospitalisation rates associated with the 10-year age cohorts studied. These estimates were taken from Table 1 of the 29 July 2020 report of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling, Operational sub-group (SPI-M-O). The proportion of ICU cases to hospitalisations was calculated using the PHE Benefit Estimation for COVID-19 Report from 3 April 2021 which gave more recent ICU figures than the July 2020 report – the proportion of COVID-19 patients going into ICU has fallen as treatments have improved. The 10-year age cohorts were determined by weighted averages if not directly available. A fixed vaccine efficacy of 80% for all age groups for ICU reduction was used.

For the potential harms: numbers of cases of the blood clot reactions provided by MHRA up to March 31st in five-year age-bands. These observed rates were smoothed using a Poisson regression on age, with log-link.

Illustration of the potential harms and benefits at a low exposure (incidence of 2 in 10,000 per day – roughly the UK in March 2021)

At medium exposure (incidence of 6 in 10,000 per day – roughly the UK in February 2021)

And at high exposure (incidence of 20 in 10,000 per day – roughly the UK at the height of the second wave)

These illustrations show the approximate balance as it would be for people of different ages, over 16 weeks, at three different exposures to the virus (which would depend on local prevalence of the virus and how much an individual was exposed to other people who might be carrying it). People with underlying health conditions that increase their risk of a poor outcome from COVID-19 would have a higher benefit from the vaccine than illustrated for their age-range.

It is very important to note that the benefits shown are approximate, as taken at a constant level of exposure to the virus over 16 weeks (very few in the UK would be likely to experience 16 weeks at the highest exposure rate). A vaccinated person will keep accruing this benefit over the lifetime of the vaccine’s protection. The risk from vaccination occurs only at the point of vaccination. This means that over time, the benefits will increase but the risks will not.

It is also important to note that the benefits illustrated are only for ICU admission due to COVID-19. For every 1 person shown as being saved from ICU admission, there are many more who might be being saved from suffering hospitalization and ‘long COVID’. We are also not illustrating the benefit of not spreading the virus to others.

When making decisions, it is also important to take into account other potential vaccines available. For example, if there were an equally effective vaccine available, immediately, that did not carry the risk of a blood clot reaction then that might swing a decision in favour of taking that vaccine in preference to the Astra-Zeneca vaccine. However, if such a vaccine were not immediately available, then the risk of exposure to the COVID-19 virus during each week of any delay before such an alternative were available would have to be weighed up in a decision whether to wait or not.

All of these factors make any decision over the Astra-Zeneca vaccine a complex one – the risk:benefit ratio varies between different people, and as prevalence of the virus changes. We hope these illustrations help make these complexities slightly clearer.