Nature NEWS FEATURE

06 September 2022

Remite Ruben Piacentini

Vaccines inhaled through the mouth or nose might stop the coronavirus in its tracks, although there’s little evidence from human trials so far.

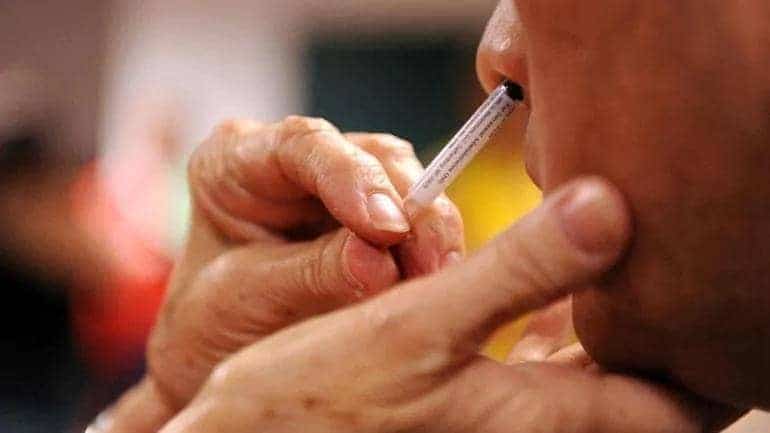

A student in Washington DC receives an influenza nasal-spray vaccine, in 2009. Intranasal and oral COVID-19 vaccines are now in development. Credit: Hyungwon Kang/Reuters

Editor’s note: Indian regulators approved Bharat Biotech’s intranasal vaccine for emergency use on 6 September.

Are sprays the future of COVID-19 vaccines?

That’s the hope of dozens of research groups and companies working on new kinds of inoculation. Rather than relying on injections, these use sprays or drops administered through the nose or mouth that aim to improve protection against the virus SARS-CoV-2.

This week, an inhaled version of a COVID-19 vaccine, produced by the Chinese company CanSino Biologics in Tianjin, was approved for use as a booster dose in China.

It’s one of more than 100 oral or nasal vaccines in development around the world. In theory, these vaccines could prime immune cells in the thin mucous membranes that line cavities in the nose and mouth where SARS-CoV-2 enters the body, and quickly stop the virus in its tracks — before it spreads. Vaccine developers hope that these ‘mucosal’ vaccines will prevent even mild cases of illness and block transmission to other people, achieving what’s known as sterilizing immunity. A few mucosal vaccines are already approved for other diseases, including a sprayable vaccine against influenza.

Evidence in animals supports the idea that sterilizing immunity can be induced against COVID-19, although data from humans are scant. Nature explains why mucosal vaccines might help to quash SARS-CoV-2, and what the latest findings mean.